Reference Lists and Tables of Content

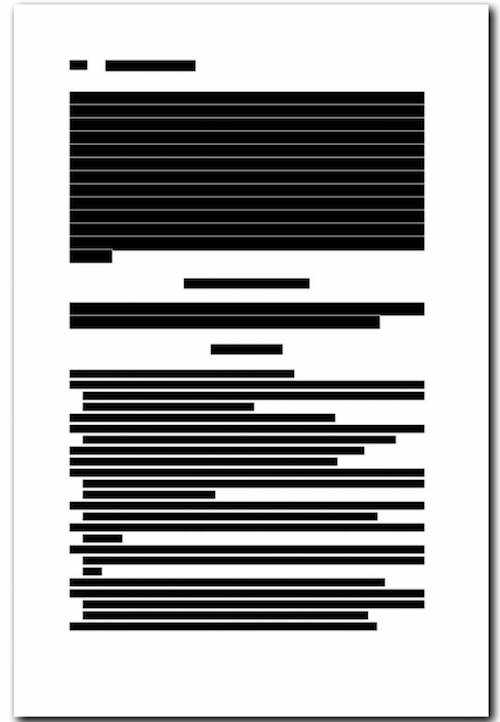

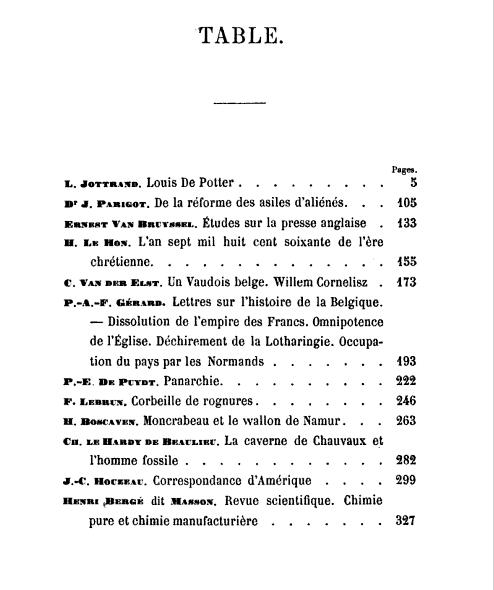

Geoff Bilder from CrossRef likes to show the following slide at scholarly conferences, and then asks the audience what they see:

Most of us probably immediately recognize this document as a scholarly article. This immediate recognition includes essential parts of an article such as the title - or the reference list:

This immediate recognition is a powerful concept, it makes it easy for the reader to navigate a scholarly document, e.g. to quickly jump to the abstract or references.

We don't have the same immediate recognition for datasets. Given that a large number of datasets in DataCite are in CSV (comma separated values) format, the closest we come to a immediately recognized document is probably the spreadsheet:

A canonical format for datasets goes beyond immediate recognition of the essential parts by the user, it would also greatly facilitate reuse of data. As Nick Stenning from the Open Knowledge Foundation (OKFN) pointed out at CSV.conf last year, the cost of shipping of goods is in large part determined by the cost of loading and unloading, and the container has dramatically changed that equation. He argued that common formats such as the OKFN data package could do the same for data reuse.

Unfortunately there are at least three problems with using spreadsheets as canonical format for datasets:

- not every dataset can be represented as a CSV file, there are many specialized formats (including of course Excel

.xlsx) - we can't include descriptive metadata (not even authors or document title) in a CSV file

- many datasets actually include a collecting of files: not only in CSV format, but also other data formats and support files such as a README.

The approach taken by the OKFN data package format - and related formats such as the Research Object Bundle - is to put all data files (in CSV or other formats) into a folder, together with a standardized machine-readable file that includes the metadata (e.g. title, authors, publication date and license). This folder can then compressed with zip, again yielding a single file (a very common approach used for example for epub and docx).

The concept described here (a collection of documents in a larger container, and a listing of all included documents) is of course at least as old as the scholarly article: the book as a canonical format for collections (of texts), and the table of contents to describe what is in the book.

The approach described here would not only help package datasets into a more reusable standard format, but the scholarly article would also greatly benefit from migrating to a container format. We all know that the concept of the scholarly article described at the beginning of this posts is falling apart - an article is simply no longer a single text document. We have not only associated figures and tables, but also associated files that can't be easily included into the article PDF, in particular files that contain the data underlying the findings of the article, but also other supplementary information.

There are currently three common approaches referencing the underlying data in a scholarly article:

- inclusion in supporting information files without any specific linking

- informal citation in the article text, most commonly in the materials and methods section

- formal citation with inclusion in the reference list

Until not too long ago I was a big proponent of including all data associated with an article in the reference list, mainly to make it easier to find the data. But the reference list isn't the appropriate place for something that is really part of the article - or as colleague Todd Vision puts it: the data generated for an article are another output rather than an input. Reference lists summarize all the inputs to an article, whereas outputs belong into a table of contents. A table of contents isn't a standard feature of scholarly articles yet, but to me is a logical next step for the journal article format, together with using the underlying concept of a container format described earlier in this post. Extracting references to datasets from a table of contents should be as easy as extracting them from a reference list, in particular if we make sure that this table of contents is openly available.

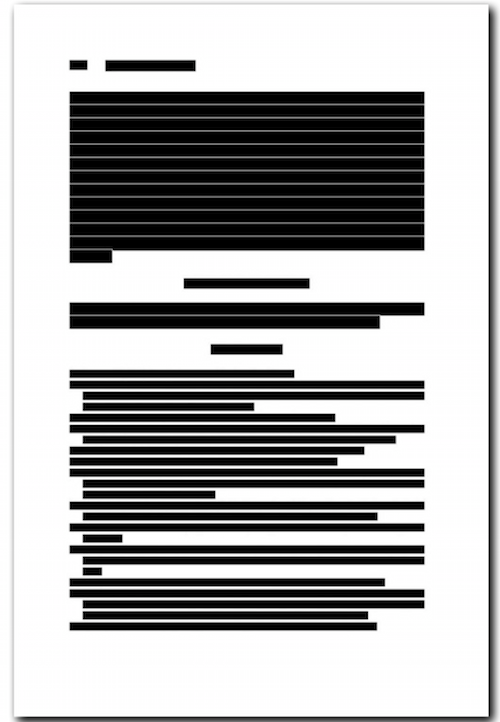

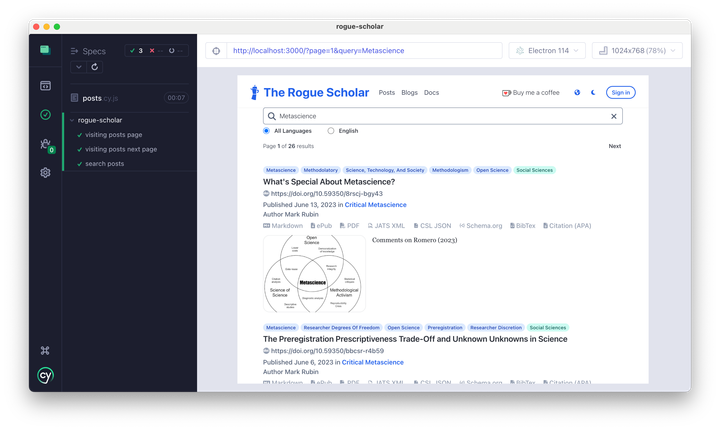

Journal Article Tag Suite (JATS) is the standard machine-readable format for journal articles in the life sciences (and increasingly other sciences). At JATS-CON in April this year I proposed (starting at minute 210) to extend JATS by providing it also as a container format:

This blog post was originally published on the DataCite Blog.

Comments ()