This blog post provides more detail for a short presentation I will give today at the Software Credit Workshop in London. The aim is to look at the infrastructure pieces needed for software discovery and credit, and at the workflows linking these different parts of the infrastructure.

Code Repository

Code repositories are the places where the actual work on software takes place, and for scientific software this often means that it happens in public with the use of an open license. Code repositories are increasingly integrated with additional services from issue trackers to continuous integration testing.

One big problem with code repositories is that they are not intended as long-term archives for code. Github and Bitbucket didn't even exist 8 years ago, and Google Code will be shut down in January 2016.

Data Repository

Long-term archiving of software is best done in dedicated data repositories, the two most popular in terms of DataCite DOIs are Zenodo (close to 5000 DOIs for software) and NanoHub (about 2,000 DOIs for software). NanoHub uses the open source HubZero software that integrates a subversion code repository, whereas Zenodo has built an integration with Github, described in this guide.

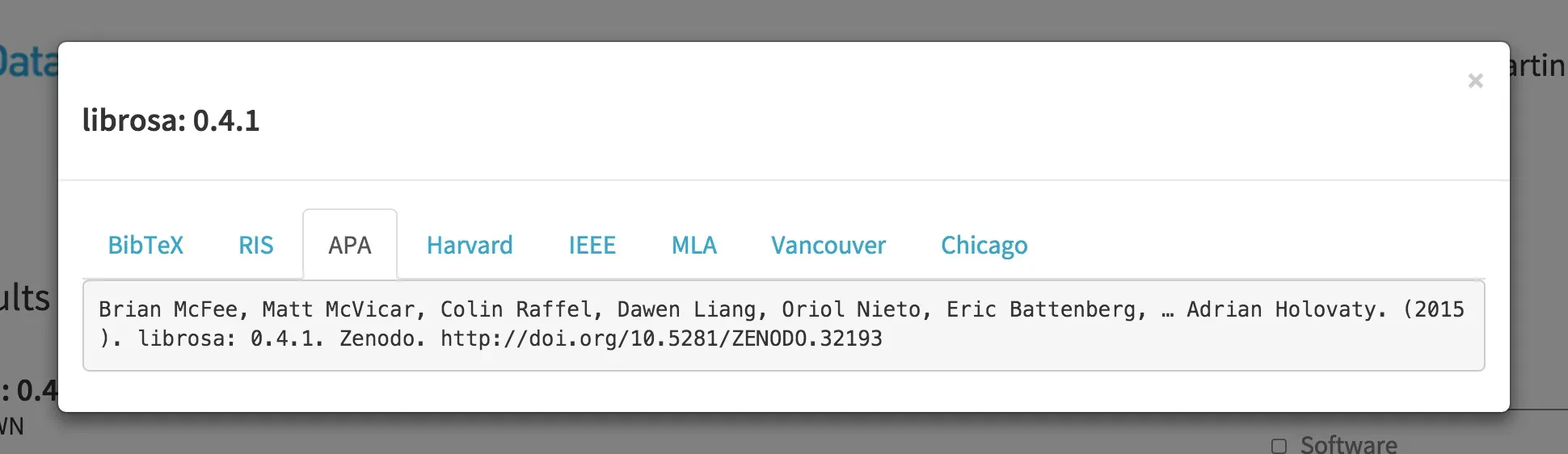

Providing a long-term archive for code is needed to properly cite software, similarly to what we expect for research data and scholarly articles. We of course don't have to use DOIs for this, but DOIs make citation easier by requiring basic citation metadata, are supported by reference managers, and we can provide formatted citations via DOI content negotiation, e.g. in DataCite Labs Search:

The Github/Zenodo integration assigns a DOI to a particular Github release of a software repo. This is perfect for a citation, which should be specific for the software version used in a particular research project. In addition, users of software and software authors want to know who is citing or otherwise re-using all versions of the software. In order for this to work we need to think beyond a specific release and link that release to other releases and to the Github repository itself. The repository has no DOI attached to it in the current workflow, so this has to be done in a service separate from the DataCite Metadata Store.

Claim Store

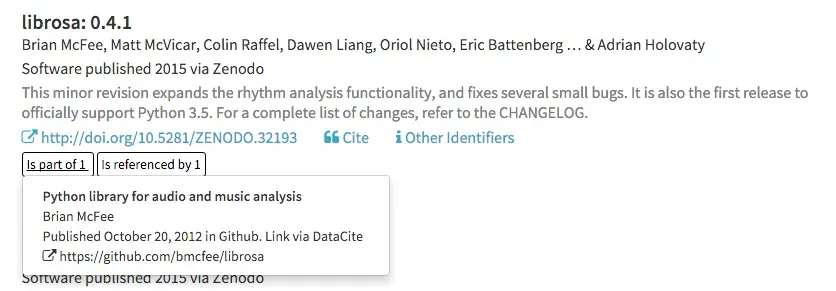

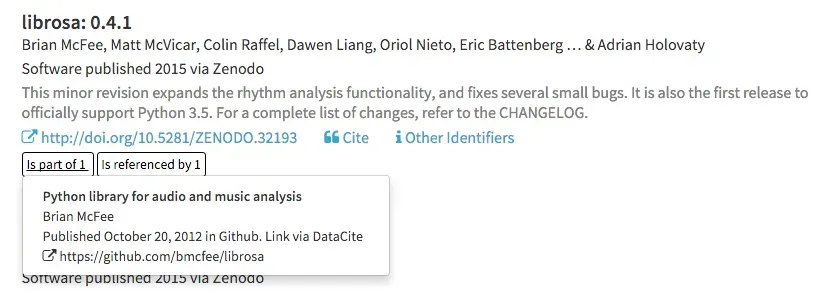

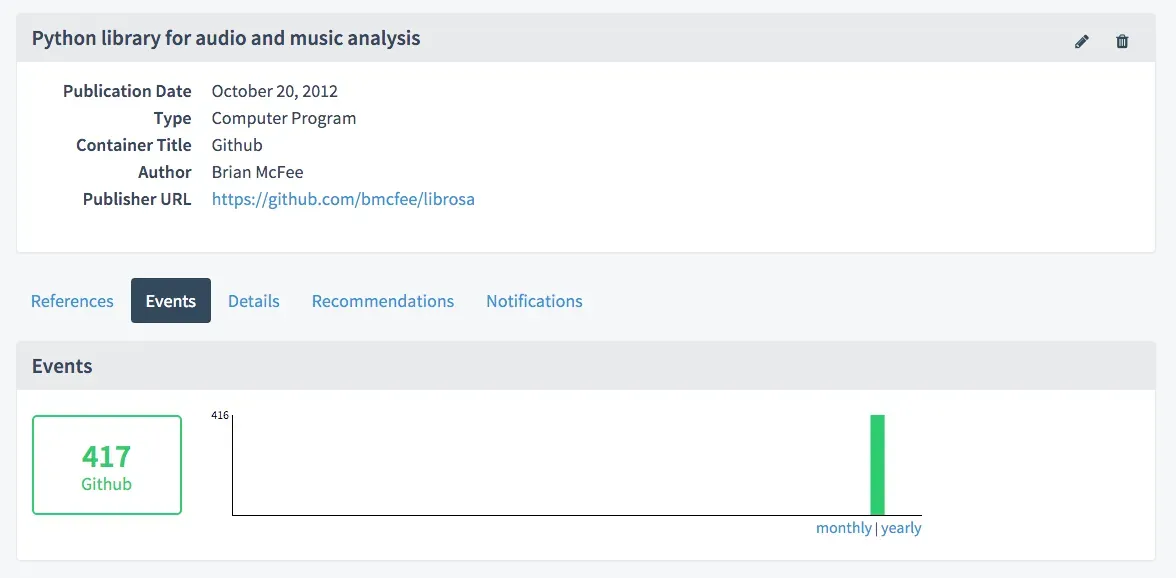

We can expand the DataCite Data-Level Metrics service or Claim Store described in an earlier post to properly handle Github repositories, and the first implementation is available now in DataCite Labs. Continuing with the earlier example of the Python librosa library, the DataCite Claim store tracks links between release, repository and repository owner:

These links are made available in DataCite Labs Search (link), so that users can go directly to either the specific release or the code repository landing page instead of the archived version on Zenodo:

We can use the claim store to not only store those links, but also to track metrics around the software package over time, e.g. the number of Github stars and forks (349 and 68 for a combined 417 in this case):

We will be building out this service in the coming months with the goal of tracking all software packages with DOIs linked to a Github release. Future iterations may also show the number of Github stars and forks directly in the search results. And because the Claim Store provides an open API, this information can also be integrated in other places, most obviously Zenodo.

Language and Domain Repository

Language-specific repositories hold all software packages from a particular language, e.g. pypi for Python or CRAN for R, with a search interface for discovery and a specific format that allows for automatic installation. Although not all scientific software is submitted to these repositories, they are usually the place that software developers go to first for discovery and installation, using a package manager working with these repositories.

Domain-specific repositories such as the Astrophysics Source Code Library (ASCL) or Bioconductor serve important roles for discovery and community building. Both their strength and limitation is their domain-specific nature. They complement the source code repositories mentioned above. One important function of domain-specific repositories is to act as a filter for scientific software. Other approaches to identify software as scientific include:

- software that has a DOI (Zenodo, above)

- software using specific tags (Depsy, see below)

- software cited in the scholarly literature (ScienceToolbox)

Metrics Data Provider

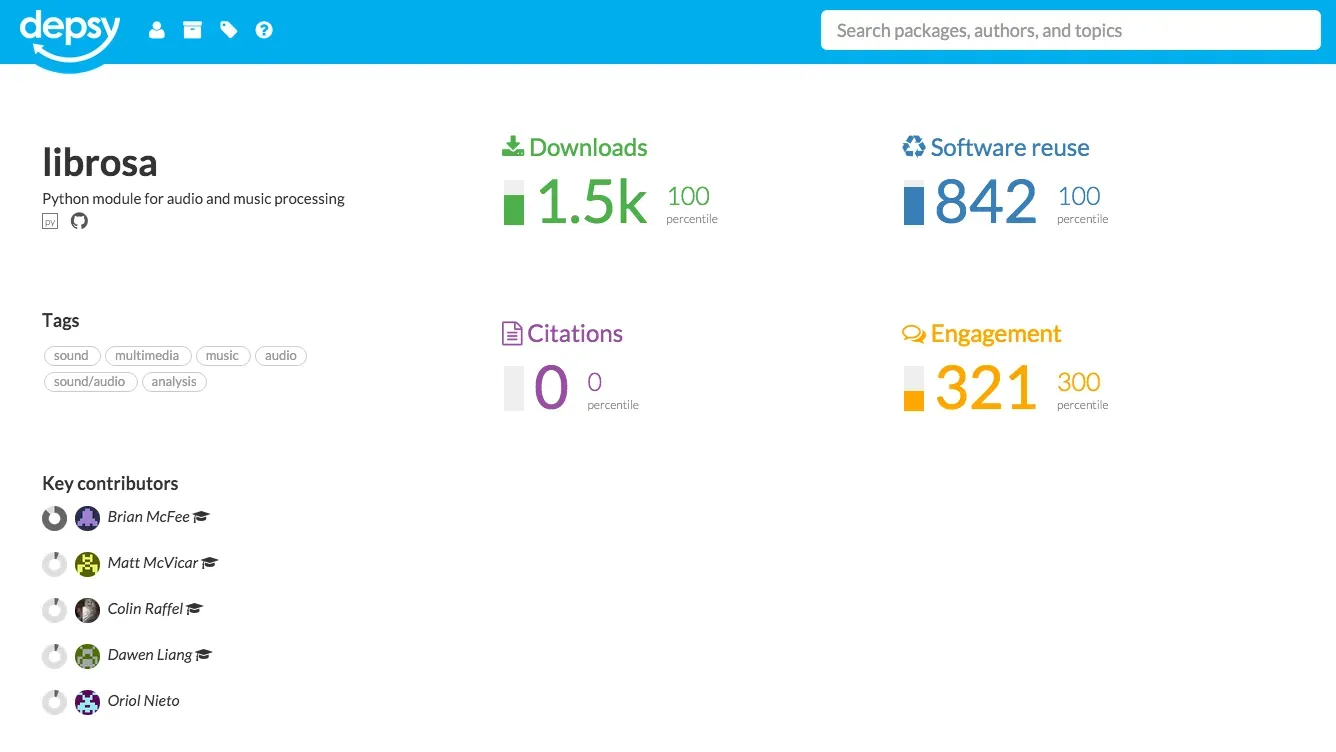

Language-specific repositories provide the detailed information that is needed to more extensively track reuse of a software package. Depsy is a new software metrics data provider by the Impactstory Team that will launch later this month, and will provide detailed information about reuse, including citations in the scholarly literature. Again using librosa as an example, Depsy provides the following information:

Of particular interest is how Depsy tracks reuse, as the service follows all the dependencies and dependencies of dependencies of a software package, described as transitive credit by Dan Katz (2014). Depsy is currently tracking software packages in pypi and CRAN, and an open API is available. Once Depsy has launched, it would of course be of great interest to integrate data from the service into the DataCite Claim Store, and Depsy is providing an open API for this.

Acknowledgments

This blog post was originally published on the DataCite Blog.

References

Transitive Credit as a Means to Address Social and Technological Concerns Stemming from Citation and Attribution of Digital Products. Journal of Open Research Software. 2014;2(1):e20. doi:10.5334/jors.be