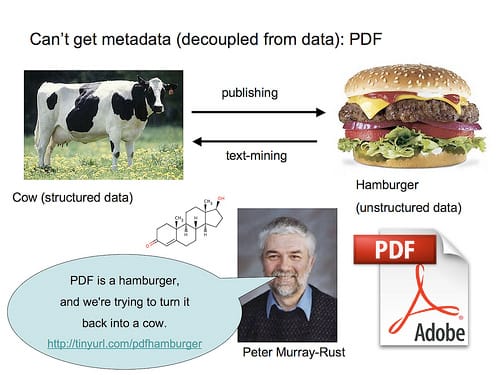

PDF has become the standard way we consume scientific papers, but in fact is not a good format for this purpose at all. Or as Martin Robbins said at the recent Science Online London conference: PDF is an insult to science. The problem was nicely illustrated by Duncan Hull, using a quote from Peter Murray-Rust from a May 2008 article:

There are of course ways journal publishers can add metadata to PDF files, e.g. using XMP markup. But that is only a workaround – what we really want is journal papers in a format that is all about document structure and not about looking good in print. XML is obviously that format with the NLM-DTD as the de facto standard for scholarly publications. Many journal publishers use that format internally, as does PubMed Central for displaying full-text papers, as well as archiving projects such as Portico.

But there are two problems with how NLM-DTD is used now. The first problem is that most scientific papers still are ultimately read as printouts of PDF files, even though most journals now are online only. I wrote in January that this reading behavior is starting to change (How do you read papers? 2010 will be different), and new article formats – such as the Article of the Future by Cell Press – and the success of the iPad are two major reasons for that.

The second problem is that there are no good NLM-DTD tools for authors. Lemon8-XML and the Microsoft Word Article Authoring Add-In are two examples that I have written about before. Publishers spend a significant amount of time and money (and using tools such as eXtyles) to convert submitted manuscripts from Microsoft Word, Open Office, or LaTeX formats into NLM-DTD. I wrote about my paper writing dream machine that would use the NLM-DTD more than two years ago. I still believe that the ideal authoring tool should be web-based, but in 2010 this should be done in HTML5 and not Adobe Flash or Microsoft Silverlight.

The two problems are obviously related. When more people are reading papers in other formats than PDF and see the advantages, it changes the idea of a scientific paper that most people have from a static document do a document that is enriched with primary research data, visualizations that use 3D and video, links to related resources, the possibility to comment, and has more than one document version. In other words, what HTML and the WWW were invented for by Tim Berners-Lee when working at CERN. At this point the incentives to create better authoring tools will be much greater, and the second problem should solve itself. And HTML and related technologies have now evolved to the point where they allow the building of some very attractive authoring tools.

Phil Bourne has written and talked a lot about this problem, including a recent editorial in PLoS Computational Biology (What do I want from the publisher of the future?) and a related SciVee video. He has also been working very hard to organize the Beyond the PDF workshop, to be held in San Diego January 19-21. The workshop website went live last week and is a very good source of information. The goal of the workshop is to identify a set of requirements and to start developing open source code that accelerates moving beyond PDF for scientific papers.

I will of course do everything possible to attend this workshop, but haven’t yet secured funding for the trip. What I hope to contribute to the Beyond the PDF project is a more intelligent use of citations (the following was also posted to the Beyond the PDF discussion group):

Unique Author Identifiers

Unique author identifiers such as ORCID not only are a big help in knowledge discovery (finding other interesting papers, datasets, etc. by the same person), but they can also help to better define the contributions of a researcher to a particular paper. This could mean a general description of the contribution (had idea for project, collected data, helped write manuscript, etc.), or could also describe a very specific contribution (researcher X did experiment Y).

Citation styles

We already have far too many citation styles, but the styles we use

have several important shortcomings. I suggest the following changes:

- Use the DOI instead of volume and page numbers whenever possible

- Use ORCID to link to the authors of the citations

- Use the Citation Typing Ontology (CiTO) to describe the meaning of the citation

- Use a note field to explain why the citation was used

Any authoring tool should obviously use the Citation Style Language (CSL) to format citations. And the citations should be provided with a CC Zero or similar license to allow reuse.

Cited by

At least as important as the citations by a particular paper are the incoming citations, the works that cite a paper. We need much better mechanisms to automate these “trackbacks”, and this should go beyond other papers and also include datasets, blog posts, etc. The incoming citations are of course very helpful for discovery, and the basis for alternative metrics.