This is the title of an upcoming workshop next Sunday organized by Ian Mulvany and myself. The workshop is a pre-conference event of the Force15 conference in Oxford. This blog post summarizes some of the issues and work that needs to be done.

Data Citation is one of the big themes of the Force15 conference, and a lot of progress has been made, including the Joint Declaration of Data Citation Principles (Data Citation Synthesis Group 2014) that start with the following paragraph on Importance:

Data should be considered legitimate, citable products of research. Data citations should be accorded the same importance in the scholarly record as citations of other research objects, such as publications.

Convincing researchers, funders, university administrators and others that data citation is important is crucial. But for researchers to actually adopt data citation to the same degree as citations of the scholarly literature, more needs to be done:

- incentives (both carrots and sticks) by funders, institutions, and scholarly societies

- training in data management

- data repositories and other tools and services for the public sharing of data

- tools and services that help citing those datasets

The focus of the workshop is on the last bullet point, and I would argue that more work still needs to be done here compared to the first three bullet points.

Reference Managers

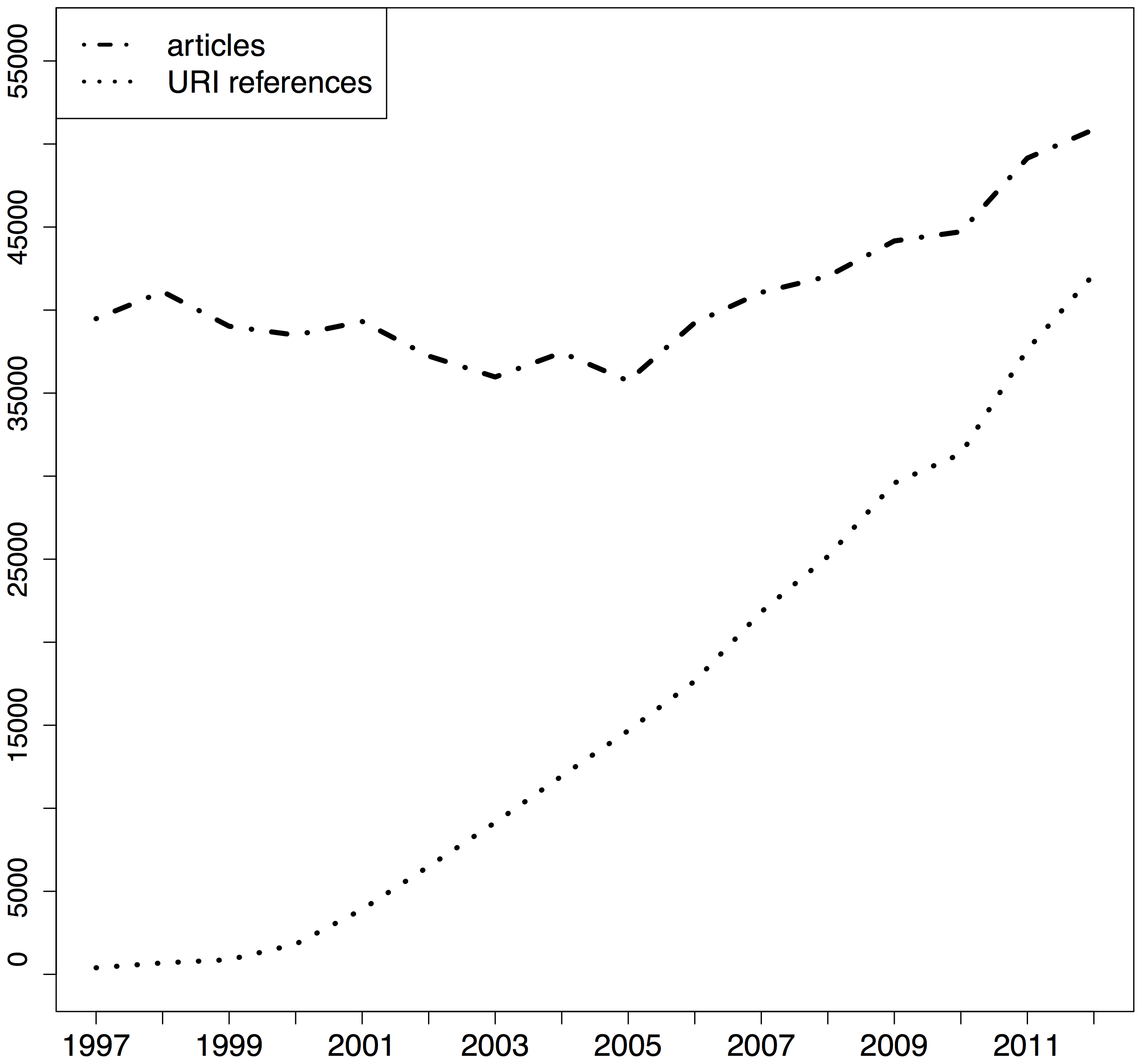

Researchers use reference managers to handle the citations in the manuscripts they write. This is both a common practice that everybody understands, and there are a plethora of tools - both free and paid - available. Most reference managers were originally built to handle citations of journal articles and maybe books or book chapters, and many of them also help with managing the associated PDF files. In the last 15 years we have seen an dramatic increase of non-article citations in reference lists, mainly to web resources (Klein et al., 2014):

References managers have started to adapt to these changes in citation patterns. Similarly they have become better in handling non-textual resources such as slide decks, datasets, or movies. Nobody should type in references by hand in 2015, as reference managers have come up with several ways of importing metadata about citations:

- import references stored in a file using a format such as BibTex or RIS

- import references by talking to an external API

- import references via a bookmarklet that grabs information from the current webpage in the browser

Endnote and Papers typically use the second approach whereas Mendeley, Zotero (and others) work almost exclusively via bookmarklets (and there are of course combinations of both). Bookmarklets in general work better for web resources and other content that is not indexed in a central service such as Web of Science or Scopus. This is also true for research data, as there are currently few central research data indexing services - the Thomson Reuters Data Citation Index and DataCite are two examples in this category. But there are also thousands of data repositories, many of them listed in re3data (Pampel et al., 2013).

The reference manager Zotero has built a large open source ecosystem around bookmarklets (what they call web translators), making it straightforward to add support for a new resource, as I have done for GenBank nucleotide sequence datasets in November after learning the basics in a webinar given by Sebastian Karcher, a frequent contributor to Zotero web translators.

There is no technical reason that reference managers can’t support a broad range of objects to cite, including datasets. And integration of data citation into the reference manager workflow is not only the easiest and most natural way for the author of a paper, but also makes it easier to discover these citations - reference lists are simply much better for that than links in the text, in particular if the content is behind subscription walls. There is a long tradition in the life sciences to put identifiers for genetic sequences used in a publication right into the text (usually into the methods section). Links in the body text are worse than references in reference lists, identifiers without a link are even worse, as they are very hard to find in an automated way (Kafkas, Kim, & McEntyre, 2013).

Please come to our workshop on Sunday afternoon if you are in Oxford and are interested in this topic. Registration is free, and the workshop will include both presentations about the current state of data citation support in the reference managers Endnote, Papers, Mendeley and Zotero, and work in smaller groups on practical implementations.

References

Kafkas, Ş., Kim, J.-H., & McEntyre, J. R. (2013). Database Citation in Full Text Biomedical Articles. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063184

Klein, M., Van de Sompel, H., Sanderson, R., Shankar, H., Balakireva, L., Zhou, K., & Tobin, R. (2014). Scholarly context not found: one in five articles suffers from reference rot. PLoS ONE, 9(12), e115253. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115253

Pampel, H., Vierkant, P., Scholze, F., Bertelmann, R., Kindling, M., Klump, J., … Dierolf, U. (2013). Making Research Data Repositories Visible: The re3data.org Registry. PLoS ONE, 8(11), e78080. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078080

Data Citation Synthesis Group. (2014). Joint Declaration of Data Citation Principles. Force11. https://doi.org/10.25490/A97F-EGYK